After experiencing both SWupdate and Mender in the past we recently got the opportunity to work with another update framework for embedded systems called RAUC.

This time the choice of RAUC as system upgrade framework was mainly motivated by the Phytec IMX6 board ecosystem which is based on both Barebox and Yocto Project.

Indeed RAUC and Barebox are both developed by Pengutronix and both are designed to provide a complete and homogeneous solution that will be introduced in this post.

Adding RAUC support in Barebox

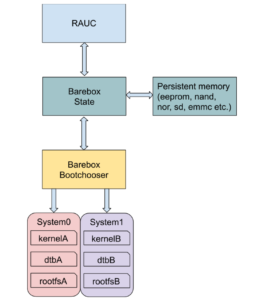

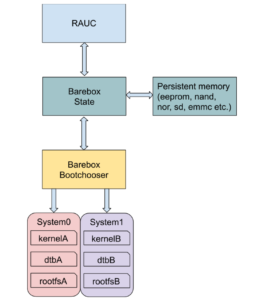

RAUC relies on the bootchooser mechanism implemented in

Barebox which provides a mean to work with abstract boot targets:

A target can be seen as set of variables and options that will be used by the bootchooser algorithm to choose which target to boot on.

The way those variables are presented and accessed is defined in the Barebox state framework which stores them in persistent memory (EEPROM, NAND/NOR flash, SD/eMMC, etc.).

In our case the state Device Tree below was already described by the Phytec BSP in the board EEPROM:

/ {

aliases {

state = &state;

};

state: imx6qdl_phytec_boot_state {

magic = <0x883b86a6>;

compatible = "barebox,state";

backend-type = "raw";

backend = <&backend_update_eeprom>;

backend-storage-type = "direct";

backend-stridesize = <54>;

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

bootstate {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

last_chosen {

reg = <0x0 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

};

system0 {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

remaining_attempts {

reg = <0x4 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <3>;

};

priority {

reg = <0x8 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <21>;

};

ok {

reg = <0xc 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <0>;

};

};

system1 {

#address-cells = <1>;

#size-cells = <1>;

remaining_attempts {

reg = <0x10 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <3>;

};

priority {

reg = <0x14 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <20>;

};

ok {

reg = <0x18 0x4>;

type = "uint32";

default = <0>;

};

};

};

};

};

&eeprom {

status = "okay";

partitions {

compatible = "fixed-partitions";

#size-cells = <1>;

#address-cells = <1>;

backend_update_eeprom: state@0 {

reg = <0x0 0x100>;

label = "update-eeprom";

};

};

};

Most of the properties are very well documented here.

This Device Tree defines a redundant A/B system upgrade scheme which matches our project requirement, we will just make sure to report remaining_attempts and priority values to the Barebox bootchooser variables that we will add later. For now we have to include the Device Tree in our board Device Tree by adding #include "imx6qdl-phytec-state.dtsi".

As we just added our state backend storage we have to enable both bootchooser and state framework in our barebox configuration:

CONFIG_STATE=y

CONFIG_STATE_DRV=y

CONFIG_CMD_STATE=y

CONFIG_BOOTCHOOSER=y

CONFIG_CMD_BOOTCHOOSER=y

We also have to add the boot targets system0 and system1 (as defined in the state Device Tree) in our default environment.

In Barebox source we create a default environment for our board in arch/arm/<board>/env with two boot entries, respectively arch/arm/<board>/env/boot/system0 and arch/arm/<board>/env/boot/system1.

Both have same contents except for the root filesystem partition name A/B:

#!/bin/sh

[ ! -e /dev/nand0.root.ubi ] && ubiattach /dev/nand0.root

mkdir -p /mnt/nand0.root.ubi.rootfsA

automount -d /mnt/nand0.root.ubi.rootfsA 'mount nand0.root.ubi.rootfsA'

global.bootm.oftree="/mnt/nand0.root.ubi.rootfsA/boot/imx6q-phytec-mira-rdk-nand.dtb"

global.bootm.image="/mnt/nand0.root.ubi.rootfsA/boot/zImage"

global.linux.bootargs.dyn.root="root=ubi0:rootfsA ubi.mtd=root rootfstype=ubifs rw"

In this configuration each partition holds its own Linux kernel image and Device Tree and the creation of the two UBIFS volumes system0/rootfsA and system1/rootfsB will be done by a factory process script.

Now we have to add bootchooser variables associated to both targets in arch/arm/<board>/env/nv directory we add following entries:

├── nv

│ ├── bootchooser.disable_on_zero_attempts

│ ├── bootchooser.reset_attempts

│ ├── bootchooser.reset_priorities

│ ├── bootchooser.retry

│ ├── bootchooser.state_prefix

│ ├── bootchooser.system0.boot

│ ├── bootchooser.system0.default_attempts

│ ├── bootchooser.system0.default_priority

│ ├── bootchooser.system1.boot

│ ├── bootchooser.system1.default_attempts

│ ├── bootchooser.system1.default_priority

│ ├── bootchooser.targets

│ ├── boot.default

The actual boot selection will be done by the bootchooser so we must set boot.default=bootchooser and targets="system0 system1".

We set a higher boot priority for system0 with variable system0.default_priority=21 over system1 with system1.default_priority=20.

We want the board to always boot on a target which means setting disable_on_zero_attempts=0 and finally we must set variable state_prefix="state.bootstate" so that the bootchooser can use our state variables stored in eeprom.

At this point we have completed the Barebox preparation and are ready to test it with RAUC.

From the Linux kernel configuration point of view we only need to add support for the SquashFS filesystem by enabling the CONFIG_SQUASHFS=y option.

Note that during our test we faced an issue with the kernel nvmem subsystem and the EEPROM. It seems that EEPROM partitions are not handled by the nvmem kernel driver because of the current binding that impose a reg property for each subnode to define a range address. The issue produces the following kernel trace at boot:

[ 2.065648] nvmem 2-00500: nvmem: invalid reg on /soc/aips-bus@2100000/i2c@21a8000/eeprom@50/partitions

Due to this, from userspace, the barebox-state tool can not read the eeprom:

root@miraq6-3d:~# barebox-state

Cannot find backend path in /imx6qdl_phytec_boot_state

Thanks to Ahmad Fatoum we’ve been able to fix this behavior with the patch series he submitted to the Linux kernel at https://lkml.org/lkml/2020/4/28/411.

Yocto integration

Adding RAUC support to our Yocto BSP is quite straightforward, we just add the meta-rauc layer:

$ git clone git://github.com/rauc/meta-rauc

$ bitbake-layers add-layer meta-rauc

Now we create a bundle image recipe recipes-core/bundles/bootlin-bundle.bb for our RAUC updates. The bundle images are the ones that RAUC can deploy on the target for system upgrades.

inherit bundle

RAUC_BUNDLE_COMPATIBLE = "bootlin"

RAUC_BUNDLE_SLOTS = "rootfs"

RAUC_SLOT_rootfs = "bootlin-image"

RAUC_KEY_FILE = "${YOCTOROOT}/keys/bootlindev.key.pem"

RAUC_CERT_FILE = "${YOCTOROOT}/keys/bootlindev.cert.pem"

The bundle image is a SquashFS filesystem composed with the root filesystem image, a manifest and the signature. At this time, RAUC supports two types of bundle formats: plain and a new format called verity that allows authentication of the installed filesystem.

Here the RAUC_SLOT_rootfs must correspond to an existing image in your BSP layer. RAUC allow signing and verifying bundle image with OpenSSL certificates provided by RAUC_CERT_FILE.

Next step, we add a configuration file in recipes-core/rauc/files/system.conf that will define the RAUC configuration on the target:

[system]

compatible=bootlin

bootloader=barebox

[keyring]

path=bootlindev.cert.pem

[slot.rootfs.0]

device=/dev/ubi0_0

type=ubifs

bootname=system0

[slot.rootfs.1]

device=/dev/ubi0_1

type=ubifs

bootname=system1

The bootname for each slot must correspond to those defined in the state Device Tree and bootchooser targets.

After that we append to the rauc recipe using a bbappend such as recipes-core/rauc/rauc_%.bbappend to install our own RAUC configuration:

FILESEXTRAPATHS_prepend := "${THISDIR}/files:"

SRC_URI += "file://system.conf"

We also have to add the rauc client package to our target image with IMAGE_INSTALL += "rauc" and we’re now ready to create our bundle image and test it:

$ bitbake bootlin-bundle

On the target we can start by checking our bundle image:

root@miraq6-3d:~# rauc info bootlin-bundle-miraq6-3d.raucb

rauc-Message: 11:27:53.354: Reading bundle: bootlin-bundle-miraq6-3d.raucb

rauc-Message: 11:27:53.544: Verifying bundle...

Compatible: 'bootlin'

Version: '1.0'

Description: 'bootlin-bundle version 1.0-r0'

Build: '20200724101202'

Hooks: ''

1 Image:

(1) bootlin-image-miraq6-3d.tar.gz

Slotclass: rootfs

Checksum: 4d3be002d7d5f4c8d4cf9d8ca7190a2b09b43ff7300943f8e9cdbcbc43c59508

Size: 111438905

Hooks:

0 Files

Certificate Chain:

0 Subject: /O=rauc Inc./CN=rauc-demo

Issuer: /O=rauc Inc./CN=rauc-demo

SPKI sha256: 18:77:3D:06:CE:63:59:AC:CC:41:87:A4:CD:14:E3:52:DA:AB:4D:BE:F5:3B:6C:06:2F:D2:0B:E2:C8:8F:08:0E

Not Before: Jul 21 07:32:37 2020 GMT

Not After: Aug 20 07:32:37 2020 GMT

Note that the target time must be set to allow the signature verification.

If the bundle image is correct we can launch the RAUC update process:

root@miraq6-3d:~# rauc install bootlin-bundle-miraq6-3d.raucb -d

rauc-Message: 11:06:01.505: Debug log domains: 'rauc'

(rauc:464): rauc-DEBUG: 11:06:01.522: install started

(rauc:464): rauc-DEBUG: 11:06:01.522: input bundle: bootlin-bundle-miraq6-3d.raucb

(rauc:464): rauc-DEBUG: 11:06:01.606: Trying to contact rauc service

installing

0% Installing

0% Determining slot states

20% Determining slot states done.

20% Checking bundle

20% Verifying signature

40% Verifying signature done.

40% Checking bundle done.

40% Loading manifest file

60% Loading manifest file done.

60% Determining target install group

80% Determining target install group done.

80% Updating slots

80% Checking slot rootfs.1

90% Checking slot rootfs.1 done.

90% Copying image to rootfs.1

...

100% Copying image to rootfs.1 done.

After reboot we finally check the RAUC boot status:

root@miraq6-3d:~# rauc status

=== System Info ===

Compatible: bootlin

Variant:

Booted from: rootfs.1 (system1)

=== Bootloader ===

Activated: rootfs.0 (system0)

Note that in this example we only use the RAUC CLI client but you can also use the D-Bus API or the rauc-hawkbit client interfacing with hawkBit

webserver.

Conclusion

This RAUC integration allows us to achieve our system upgrade framework tour and we can say that this project compares very well with other system upgrade frameworks.

Indeed the fact that Barebox and RAUC are both developed by Pengutronix helps a lot for the integration but it is also well supported in U-Boot and doesn’t need much more than a boot script to integrate RAUC on it at least for a simple A/B upgrade strategy.

The SIDO is a large event dedicated to IoT, AI, robotics in Paris, and it takes place next to the Open Source Experience event, which as the name suggest is dedicated to all things related to open-source. For Bootlin whose activity is precisely at the junction between embedded systems/IoT and open-source, being present at this combined event made complete sense.

The SIDO is a large event dedicated to IoT, AI, robotics in Paris, and it takes place next to the Open Source Experience event, which as the name suggest is dedicated to all things related to open-source. For Bootlin whose activity is precisely at the junction between embedded systems/IoT and open-source, being present at this combined event made complete sense.