Like most of us, due to the Covid-19 epidemic, you may be forced to work from home. To take advantage from this time confined at home, we are now proposing all our training courses as online seminars. You can then benefit from the contents and quality of Bootlin training sessions, without leaving the comfort and safety of your home. During our online seminars, our instructors will alternate between presentations and practical demonstrations, executing the instructions of our practical labs.

Like most of us, due to the Covid-19 epidemic, you may be forced to work from home. To take advantage from this time confined at home, we are now proposing all our training courses as online seminars. You can then benefit from the contents and quality of Bootlin training sessions, without leaving the comfort and safety of your home. During our online seminars, our instructors will alternate between presentations and practical demonstrations, executing the instructions of our practical labs.

At any time, participants will be able to ask questions.

We can propose such remote training both through public online sessions, open to individual registration, as well as dedicated online sessions, for participants from the same company.

Public online sessions

We’re trying to propose time slots that should be manageable from Europe, Middle East, Africa and at least for the East Coast of North America. All such sessions will be taught in English. As usual with all our sessions, all our training materials (lectures and lab instructions) are freely available from the pages describing our courses.

Our Embedded Linux and Linux kernel courses are delivered over 7 half days of 4 hours each, while our Yocto Project, Buildroot and Linux Graphics courses are delivered over 4 half days. For our embedded Linux and Yocto Project courses, we propose an additional date in case some extra time is needed to complete the agenda.

Here are all the available sessions. If the situation lasts longer, we will create new sessions as needed:

| Type |

Dates |

Time |

Duration |

Expected trainer |

Cost and registration |

| Embedded Linux (agenda) |

Sep. 28, 29, 30, Oct. 1, 2, 5, 6 2020. |

17:00 – 21:00 (Paris), 8:00 – 12:00 (San Francisco) |

28 h |

Michael Opdenacker |

829 EUR + VAT* (register) |

| Embedded Linux (agenda) |

Nov. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 12, 2020. |

14:00 – 18:00 (Paris), 8:00 – 12:00 (New York) |

28 h |

Michael Opdenacker |

829 EUR + VAT* (register) |

| Linux kernel (agenda) |

Nov. 16, 17, 18, 19, 23, 24, 25, 26 |

14:00 – 18:00 (Paris time) |

28 h |

Alexandre Belloni |

829 EUR + VAT* (register) |

| Yocto Project (agenda) |

Nov. 30, Dec. 1, 2, 3, 4, 2020 |

14:00 – 18:00 (Paris time) |

16 h |

Maxime Chevallier |

519 EUR + VAT* (register) |

| Buildroot (agenda) |

Dec. 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11, 2020 |

14:00 – 18:00 (Paris time) |

16 h |

Thomas Petazzoni |

519 EUR + VAT* (register) |

| Linux Graphics (agenda) |

Dec. 1, 2, 3, 4, 2020 |

14:00 – 18:00 (Paris time) |

16 h |

Paul Kocialkowski |

519 EUR + VAT* (register

|

* VAT: applies to businesses in France and to individuals from all countries. Businesses in the European Union won’t be charged VAT only if they provide valid company information and VAT number to Evenbrite at registration time. For businesses in other countries, we should be able to grant them a VAT refund, provided they send us a proof of company incorporation before the end of the session.

Each public session will be confirmed once there are at least 6 participants. If the minimum number of participants is not reached, Bootlin will propose new dates or a full refund (including Eventbrite fees) if no new date works for the participant.

We guarantee that the maximum number of participants will be 12.

Dedicated online sessions

If you have enough people to train, such dedicated sessions can be a worthy alternative to public ones:

- Flexible dates and daily durations, corresponding to the availability of your teams.

- Confidentiality: freedom to ask questions that are related to your company’s projects and plans.

- If time left, possibility to have knowledge sharing time with the instructor, that could go beyond the scope of the training course.

- Language: possibility to have a session in French instead of in English.

Online seminar details

Each session will be given through Jitsi Meet, a Free Software solution that we are trying to promote. As a backup solution, we will also be able to Google Hangouts Meet. Each participant should have her or his own connection and computer (with webcam and microphone) and if possible headsets, to avoid echo issues between audio input and output. This is probably the best solution to allow each participant to ask questions and write comments in the chat window. We also support people connecting from the same conference room with suitable equipment.

Each participant is asked to connect 15 minutes before the session starts, to make sure her or his setup works (instructions will be sent before the event).

How to register

For online public sessions, use the EventBrite links in the above list of sessions to register one or several individuals.

To register an entire group (for dedicated sessions), please contact training@bootlin.com and tell us the type of session you are interested in. We will then send you a registration form to collect all the details we need to send you a quote.

You can also ask all your questions by calling +33 484 258 097.

Questions and answers

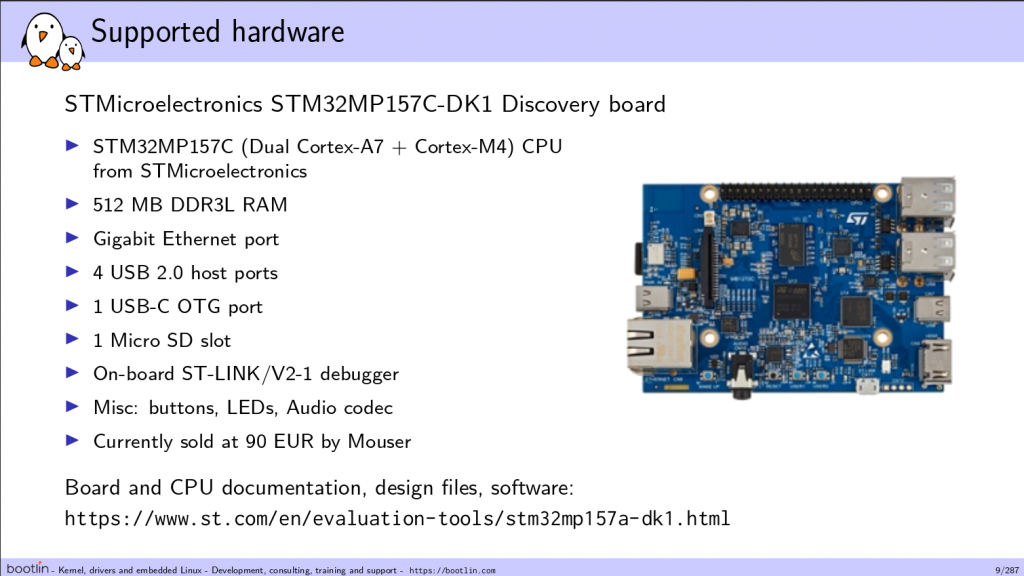

Q : Should I order hardware in advance, our hardware included in the training cost?

R : No, practical labs are replaced by technical demonstrations, so you will be able to follow the course without any hardware. However, you can still order the hardware by checking the “Shopping list” pages of presentation materials for each session. This way, between each session, you will be able to replay by yourself the labs demonstrated by your trainer, ask all your questions, and get help between sessions through our dedicated Matrix channel to reach your goals.

Q: Why just demos instead of practicing with real hardware?

A: We are not ready to support a sufficient number of participants doing practical labs remotely with real hardware. This is more complicated and time consuming than in real life. Hence, what we we’re proposing is to replace practical labs with practical demonstrations shown by the instructor. The instructor will go through the normal practical labs with the standard hardware that we’re using.

Q: Would it be possible to run practical labs on the QEMU emulator?

R: Yes, it’s coming. In the embedded Linux course, we are already offering instructions to run most practical labs on QEMU between the sessions, before the practical demos performed by the trainer. We should also be able to propose such instructions for our Yocto Project and Buildroot training courses in the next months. Such work is likely to take more time for our Linux kernel course, practical labs being closer to the hardware that we use.

Q: Why proposing half days instead of full days?

A: From our experience, it’s very difficult to stay focused on a new technical topic for an entire day without having periodic moments when you are active (which happens in our public and on-site sessions, in which we interleave lectures and practical labs). Hence, we believe that daily slots of 4 hours (with a small break in the middle) is a good solution, also leaving extra time for following up your normal work.

Like most of us, due to the Covid-19 epidemic, you may be forced to work from home. To take advantage from this time confined at home, we are now proposing all our training courses as online seminars. You can then benefit from the contents and quality of Bootlin

Like most of us, due to the Covid-19 epidemic, you may be forced to work from home. To take advantage from this time confined at home, we are now proposing all our training courses as online seminars. You can then benefit from the contents and quality of Bootlin