In the past months, the Linux kernel driver for the Ethernet MAC found in a number of Marvell SoCs, mvneta, has seen quite a few improvements. Lorenzo Bianconi brought support for XDP operations on non-linear buffers, a follow-up work on the already-great XDP support that offers very nice performances on that controller. Russell King contributed an improved, more generic and easier to maintain phylink support, to deal with the variety of embedded use-cases.

At that point, it’s getting difficult to squeeze more performances out of this controller. However, we still have some tricks we can use to improve some use-cases so in the past months, we’ve worked on implementing QoS features on mvneta, through the use of mqprio.

Multi-queue support

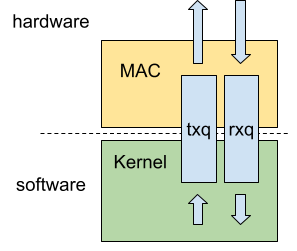

A simple Ethernet NIC (Network Interface Controller) could be described as a controller that handles some protocol-level aspect of the Ethernet standard, where the incoming and outgoing packets would be enqueued in a dedicated ring-buffer that serves as an interface between the controller and the kernel.

The buffer containing packets that needs to be sent is called the Transmit Queue, often written as txq. It’s fed by the kernel, where the NIC driver converts some struct sk_buff objects called skb, that represent packets trough their journey in the kernel, into buffers that are enqueued in the txq.

On the ingress side, the Receive Queue, written rxq, is fed by the MAC, and dequeued by the NIC driver, who creates skb containing the payload and attached metadata.

In the end, every incoming or outgoing packet is enqueued and dequeued in a typical first-in first-out fashion. When the queue is full, packets are dropped, everything is neat, simple and deterministic.

However, typical use-cases are never simple. Most modern NICs have several queues in TX and RX. On the receive side, it’s useful to have multiple queues for performance reasons. When receiving packets, we can spread the traffic across multiple queues (with RSS for example), and have one CPU core dedicated to each queue. More complex use-cases can be expressed, such as flow steering, that you can learn about in the kernel documentation.

On the transmit side, it’s a bit less obvious why we want to have multiple queues. If the CPU is the bottleneck in terms of performances, having multiple TX queues won’t help much. Still, there are ways to benefit from having multiple TX queues on a multi-cpu system with XPS.

However, when the line-rate is the bottleneck, having multiple queues gets useful. By sorting the outgoing traffic by priority and assign each priority to a TX queue, the NIC can then pick the next packet to send from the highest priority queue until it’s empty, and then move on to the next priority. That way, we implement what’s called QoS (Quality of Service), where we care about high-priority traffic making it through the controller.

QoS itself is useful for various reasons. Besides the obvious prioritization of high-value streams for not-so-neutral networking, we can also imagine tagging management traffic as high-priority, to guarantee the ability to remotely access a machine under heavy traffic.

Other applications can be in the realm of Time Sensitive Networking, where it’s important that time-sensitive traffic gets sent right-away, using the high-priority queues as shortcuts to bypass the low-priority over-crowded queues.

NICs can use more advanced algorithms to pick the queue to de-queue the packet from, in a process called arbitration, to give low-priority traffic a chance to get sent even when high-priority traffic takes most of the bandwidth.

Typical algorithms range from strict priority-based FIFO to more flexible Weighted Round-Robin arbitration, to allow at least a few low-priority packets to leave the NIC.

In the case of mvneta, we’re limited in terms of what we can do in the receive path. Most of the work we’ve done focused on the transmit side.

Traffic Priorisation and Arbitration

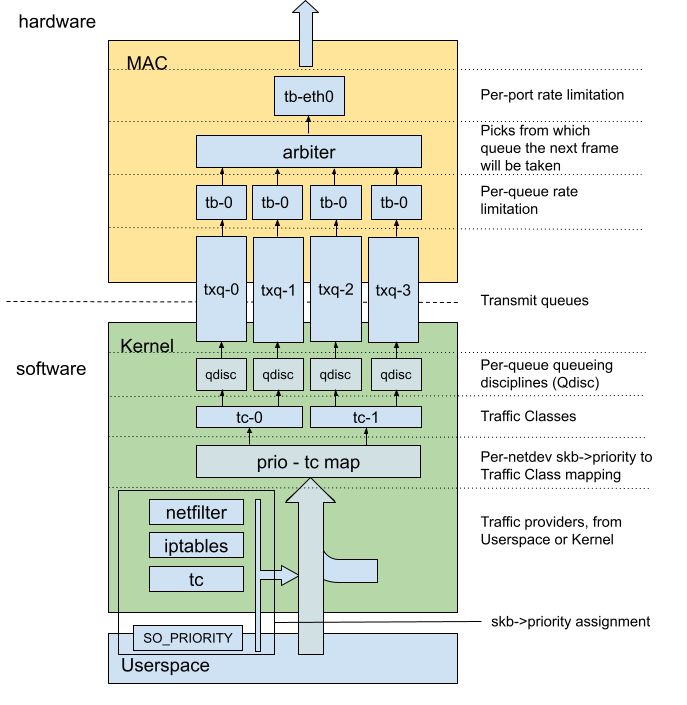

Multi-queue support on the TX path is a three-fold process.

First, we have to know which packets are high-priority and which aren’t, by assigning a value to the skb->priority field.

There are several ways of doing so, using iptables, nftables, tc, socket parameters through SO_PRIORITY, or switching parameters. This is outside of the scope of this article, we’ll assume that incoming packets are already prioritized through one of the above mechanisms.

Once the packet comes into the network stack as a skb, we need to assign it to a TX queue. That’s where tc-mqprio comes in play.

In that second step, we build a mapping between priorities and queues. This mapping is done through the use of an intermediate mapping, the Traffic Classes. A Traffic Class is a mapping between N priorities and M transmit queues. We therefore have 2 levels of mappings to configure :

- The priority to Traffic Class mapping (N to 1 mapping)

- The Traffic Class to TX queue mapping (1 to M mapping)

All of this is done in one single tc command. We’re not going to dive too much into the tc tool itself, but we’ll still see a bit how tc-mqprio works.

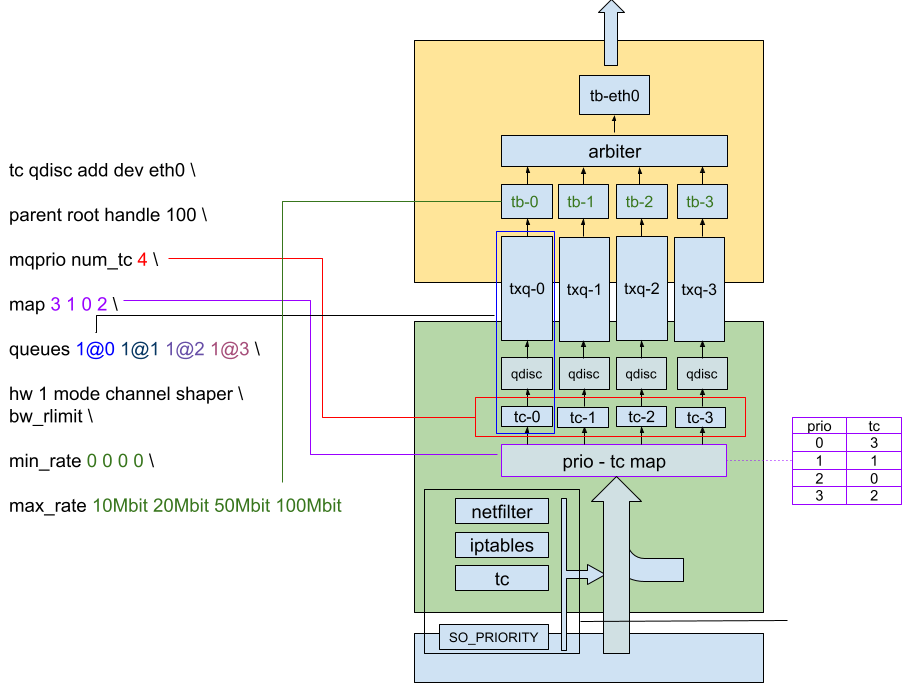

Here’s an example :

tc qdisc add dev eth0 parent root handle 100 mqprio num_tc 8 map 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 queues 1@0 1@1 1@2 1@3 1@4 1@5 1@6 1@7 hw 1

Let’s break this down a bit.

Queuing Disciplines (QDiscs) are algorithms you use to select how and when you enqueue and dequeue traffic on a NIC. It benefits from great software support, but can also be offloaded to hardware, as we’ll see.

So the first part of the command is about attaching the mqprio QDisc to the network interface :

tc qdisc add dev eth0 parent root handle 100 mqprio

After that, we configure the traffic classes. Here, we create 8 traffic classes :

num_tc 8

And then we map each class to a priority. In this list, the n-th element corresponds to the class you want to assign to priority n. Here, we map the 8 first priorities to a dedicated class. Priorities that aren’t assigned a class are mapped to the class 0.

map 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Finally, we map each class to a queue. Classes can only be assigned a contiguous set of queues, so the only parameters needed for the mapping are the number of queues assigned to the class (the number before the @), and the offset in the queue list (after the @). We specify one mapping per class, the m-th element in the list being the mapping for class number m. In the following example, we simply assign one queue per traffic class :

queues 1@0 1@1 1@2 1@3 1@4 1@5 1@6 1@7

Under the hood, tc-mqprio will actually assign one QDisc per queue and map the Traffic Classes to these QDiscs, so that we can still hook other tc configurations on a per-queue basis.

Finally, we enable hardware offloading of the prioritization :

hw 1

The last part of the work consists in configuring the hardware itself to correctly prioritize each queue. That’s done by the NIC driver, which gets the configuration from the tc hooks.

If we take a look at the Hardware, we see that the queues are exposed to the kernel, which will enqueue packets into them. Each queue then has a Bandwidth Limiter, followed by the arbitration layer. Finally, we have one last global Rate limiter, and the path then continues to the egress blocks of the controller.

The arbiter configuration is easy, it’s just a matter of enabling the strict priority arbitration in a few registers.

Let’s summarize what the stack looks like :

Traffic shaping

Being able to prioritize outgoing traffic is good, but we can step-it up by allowing to limit the rate on each queue. That way, we can neatly organize and control how we want to use our bandwidth, not on a per-packet level but really on a bits/s basis.

Controlling the rate of individual flows or queues is called Traffic Shaping. When configuring a shaper, not only do we focus on the desired max rate, but also how we deal with traffic bursts. We can smooth them by tightly controlling how and when we send packets, or we can allow some burstiness by being more lenient on how often we enforce the rate limitation.

In the mvneta hardware, we have 2 levels of shaping : one level of per-queue shapers, and one per-port shaper. They can all be controlled semi-independently, some parameters being shared between all shapers.

With mqprio, the shapers are configured on a per-Traffic-Class basis. Since the hardware only allows per-queue shaping, we enforce in the driver that one traffic class is assigned to only one queue.

A final configuration with mqprio looks like this :

Most shapers use a variant of the Token Bucket Filter algorithm. The principle is the following :

Each queue has a Token Bucket, with a limited capacity. When a packet needs to be sent, one token per bit in the packet gets taken from the bucket. If the bucket is empty, transmission stops. The bucket then gets refilled at a configurable rate, with a configurable amount of tokens.

Configuring the TBF for each queue boils down to setting a few parameters :

– The Bucket Size, sometimes called burst, buffer or maxburst.

It should be big enough to accommodate for the shaping rate required, but not too big. If the bucket is too big and you have a very slow traffic going out, the bucket is going to fill up to its full size. When you suddenly have a lot of traffic to send, you’ll first have a huge burst, the time for the bucket to empty, before the traffic starts to actually get limited. Unlike the tc-tbf interface, tc-mqprio doesn’t allow to change the burst size, so it’s up to the driver to set it.

– The Refill Rate, sometimes called tick, defining how often you refill the bucket.

– The Refill Value, defining how many tokens you put back into the bucket at each refill.

These two, combined together, define the actual rate limitation. The approach taken to select the value is to select a fixed value for one of the parameters, and vary the other one to select the desired rate. In the case of mvneta, we chose to use a fixed refill rate, and change the refill value. This means that we have a limited resolution in the rates we can express. In our case, we have a 10kbps resolution, allowing us to cover any rate limitation between 10kbps and 5Gbps, with 10k increments.

– One final parameter is the minburst or MTU parameter, and controls the minimum amount of tokens required to allow packet transmission.

Since transmission stops when the bucket is empty, we can end-up with an empty bucket in the middle of a packet being transmitted.The link-partner may not be too happy about that, so it’s common to set the Maximum Transmission Unit as the minimum amount of tokens required to trigger transmission.

That way, we are sure that when we start sending a packet, we’ll always have enough tokens in the bucket to send the full packet. We can play a bit with this parameter if we want to buffer small packets and send them in a short burst when we have enough. In our case, we simply configured it as the MTU, which is good enough for most cases.

In the end, the gains are not necessarily measurable in terms of raw performances, but thanks to mqprio and traffic shaping, we can now have better control on the traffic that comes out of our interface.

An example of configuration would be :

# Shaping and priority configuration tc qdisc add dev eth0 parent root handle 100 mqprio \ num_tc 8 map 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 \ queues 1@0 1@1 1@2 1@3 1@4 1@5 1@6 1@7 \ hw 1 mode channel shaper bw_rlimit \ max_rate 1Gbit 500Mbit 250Mbit 125Mbit 50Mbit 25Mbit 25Mbit 25MBit # Assign HTTP traffic a priority of 1, to limit it to 500Mbps iptables -t mangle -A POSTROUTING -p tcp --dport 80 -j CLASSIFY \ --set-class 0:1

There are tons of other use-cases, for example limiting per-vlan speeds, or in contrary making sure that traffic on a specific vlan has the highest priority, and all of that mostly offloaded to the hardware itself !