Table of contents

Introduction

From April 15th

to 17th 2008 took place the fourth edition of the Embedded Linux

Conference organised every year by the CE Linux Forum in the Silicon

Valley. This year, for the first time, the conference was organized

inside the Computer History

Museum, which happened to be a very nice venue for such a

conference. The museum also has various exhibits about computer

history such as Visible

Storage, an exhibit featuring many samples from the museum

collection, ranging from the first computers to the first Google

cluster, going through Cray supercomputers.

From April 15th

to 17th 2008 took place the fourth edition of the Embedded Linux

Conference organised every year by the CE Linux Forum in the Silicon

Valley. This year, for the first time, the conference was organized

inside the Computer History

Museum, which happened to be a very nice venue for such a

conference. The museum also has various exhibits about computer

history such as Visible

Storage, an exhibit featuring many samples from the museum

collection, ranging from the first computers to the first Google

cluster, going through Cray supercomputers.

The conference's

program was very promising: three keynotes from famous speakers

(Henry Kigman, Andrew Morton and Tim Bird) and fifty sessions, either

talks, tutorials of bird-of-a-feather sessions, covering a wide range

of subjects of interest for any embedded Linux developer : power

management, debugging techniques, system size reduction, flash

filesystems, embedded distributions, realtime, graphics and video,

security, etc.

This report has been written by Thomas Petazzoni, from Free Electrons. The report

only covers the talks he could actually attend : there were three

simultaneous tracks at Embedded Linux Conference. Sometimes very

interesting talks were happening at the same time, leading to a kind

of frustration for the audience, willing to be at several places at

the same time. For those people, and for all the persons who could not

attend the conferences, Free Electrons also provides video records for

19 talks given during ELC. The links to the video are given below in

the report. The following report makes an extensive use of the

contents of the slides used by the speakers during their talks.

Day 1

Keynote: Tux in Lights, Henry Kigman

Link to the video

(44 minutes, 139 megabytes) and the slides.

The first day of the conference

was opened by a keynote of Henry Kigman entitled Tux in

Lights. Henry Kigman is famous for being the editor behing the

well-known Linux Devices

website, and he was this year in charge of opening the Embedded Linux

Conference. He started his talk with an introduction about the

importance of such meetings : he emphasized the fact that many

free software developers work together all year long without having

the chance to meet in person. In that respect, conferences such as ELC

are important moment to see each other, he said.

The first day of the conference

was opened by a keynote of Henry Kigman entitled Tux in

Lights. Henry Kigman is famous for being the editor behing the

well-known Linux Devices

website, and he was this year in charge of opening the Embedded Linux

Conference. He started his talk with an introduction about the

importance of such meetings : he emphasized the fact that many

free software developers work together all year long without having

the chance to meet in person. In that respect, conferences such as ELC

are important moment to see each other, he said.

Kigman then continued his presentation with slides containing the

result of the latest Linux Devices survey concerning the use of embedded Linux, that

Jake Edge already reported on Linux Weekly News in his article ELC: Trends in embedded

Linux.

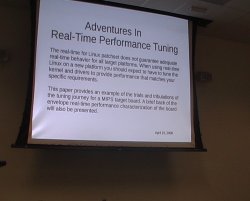

Adventures in Real-Time Performance Tuning, Frank Rowand

Link to the video

(50 minutes, 251 megabytes) and the slides.

In this talk, Frank Rowand presented what has been involved in

setting up the real time version of the Linux kernel (linux-rt) on a MIPS platform,

using the TX4937 processor. He started by reminding that doesn't mean

fast response time, but determinism, and that deadlines could be

seconds, milliseconds or microseconds, for example.

Then, he summed up

what could affect the IRQ latency in the Linux kernel : disabled

interrupts, execution of top halves, softirqs, scheduler execution,

and finally context switch. An important aspect of Linux RT is tuning

this IRQ latency to make it 1) deterministic and 2) low. So, code

disabling interrupts in the kernel should be avoided as much as

possible, and Frank's talk focused on finding and fixing issues about

such pieces of code.

Then, he summed up

what could affect the IRQ latency in the Linux kernel : disabled

interrupts, execution of top halves, softirqs, scheduler execution,

and finally context switch. An important aspect of Linux RT is tuning

this IRQ latency to make it 1) deterministic and 2) low. So, code

disabling interrupts in the kernel should be avoided as much as

possible, and Frank's talk focused on finding and fixing issues about

such pieces of code.

The roadmap of his adventure was basically :

- Add some RT pieces for MIPS and the tx4937 processor

- Add MIPS support to RT instrumention. Instrumentation is an

essential tool to find RT-related issues, he said.

- Tuning.

- Implement "lite" irq disabled instrumentation, because the

existing instrumentation tools overhead was too high in his

opining.

- Tuning.

He then started to talk about the latency tracer, which has been

recently submitted to mainline inclusion by Ingo Molnar. Currently

only available in the -rt, this tracer has recently been

improved in several areas in 2.6.24-rt2 : cleaned up code,

user/kernel interface based on debugfs instead of /proc,

simultaneous trace of IRQ off and preempt off latencies, and

simultaneous histogram and trace. He however used the previous

version, 2.6.24-rt1 for the experiments reported in his talk.

His first experiments with the tracer lead to the discovery of

several issues :

- Latencies up to 5.7 seconds were showing up in

/proc/latency_hist/interrupt_off_latency/CPU0. Using

/proc/latency_trace, he discovered the culprit :

r4k_wait_irqoff(), a MIPS-specific function called when

the CPU is idle. That function was disabling interrupts before going

into idle using the wait MIPS instruction. The quick

fix was to use the nowait

kernel option, to disable the use of CPU idle specific

instructions. Of course, one must be aware of the consequences of

using such an option from a power management perspective. The real

fix would be to stop latency tracing in cpu_idle(), as

is done on x86. Even with that fix, he still had some

large maximum latencies.

- CPUs have timestamps registers that are very accurate,

and 64 bits or 32 bits wide. These registers are incremented at each

cycle, and on MIPS, he used 32 bits counters are used, which means

that hese counters were overflowing after a few seconds. In his

case, it was rolling over in around six seconds (very close to the

maximum 5.7 seconds reported latency !). In fact, it happened that

the latency tracer code didn't handle clock rollover properly. He

fixed that by using the same algorithms used for jiffies in

include/linux/jiffies.h. This fix removed the maximum

reported latencies, and he was now down at 6.7 milliseconds maximum

latency.

- The remaining problems were due to the fact that the timer

comparison and capture code was not handling properly

the switch between raw and non-raw clock sources. So in

kernel/latency_trace.c, he had to check for switch

between raw and non-raw clock sources, and at any switch, delete

timestamps in other mode from the current event.

He then showed some nice and pretty graphs (visible in the video),

showing the improvements made by each fix. Once that the very ugly

latencies were fixed, the things to do next is to fix the thing that

disables preemption for the longest time and the thing that disables

interrupts for the longest time. In his talk, he focused on the

second part : irq disabled time.

He presented in

more details the main tool used for that debugging : the latency

tracer. He described the contents of a latency trace output, which

might be kernel-hacker-readable, but not necessarly human-readable at

first sight. He highlighted the fact that the function trace that one

can get with the latency tracer is not a list of all functions

executed, but that trace points are only instered at "interesting"

locations in various subsystems. Thus, one has to interpolate what's

happening between the locations provided by the trace, he said. He

also mentionned the usefulness of the data fields available for each

line of trace : they are not documented in any way, are specific

to each trace point, but end up to be very useful in understanding

what's happening. They contain informations such as time for timer

related functions or PID and priority for scheduling related

functions.

He presented in

more details the main tool used for that debugging : the latency

tracer. He described the contents of a latency trace output, which

might be kernel-hacker-readable, but not necessarly human-readable at

first sight. He highlighted the fact that the function trace that one

can get with the latency tracer is not a list of all functions

executed, but that trace points are only instered at "interesting"

locations in various subsystems. Thus, one has to interpolate what's

happening between the locations provided by the trace, he said. He

also mentionned the usefulness of the data fields available for each

line of trace : they are not documented in any way, are specific

to each trace point, but end up to be very useful in understanding

what's happening. They contain informations such as time for timer

related functions or PID and priority for scheduling related

functions.

The first problem he found with latencies of 164 microseconds

occured when handling the timer interrupt, in

hrtimer_interrupt(). Several calls to

try_to_wake_up() where made, causing a long time with

interrupt disabled (between handle_int(), the low level

interrupt handling function in MIPS that disables interrupts, and

schedule(), which re-enables interrupts). In fact, the

timer code was waking up the tasks for which timers have expired,

which is an O(n) algorithm that depends on the number of timers in the

system. He has no fix yet, except the workaround of not using to many

timers at the same time.

The second problem he found is the fact that the interrupt top half

handling followed by preempt_schedule_irq() is a long

path executing with interrupts disabled. A possible workaround is to

remove or rate limit non-realtime related interrupts, which in his

case where caused by the network card, due to having the root

filesystem mounted over NFS. What he tried, as a quick and dirty hack,

was to re-enable and immediatly disable again interrupts in

resume_kernel, the return from interrupt function. It is

a bad hack as it allows nested interrupts to occur, which could cause

the stack to overflow. However, he found that it improved the

latencies, and presented results confirming that.

As a moral, he said do not lose sight of the most important

metric -- meeting the real time application deadline -- while trying

to tune the components that cause latency. He mentionned LatencyTOP as a promising tool,

but also mentionned using the experts' knowledge, thanks to the web

and mailing lists. He mentionned a few recent topics of discussion on

the linux-rt-users, to show the type of discussion

occuring on this mailing list.

To conclude the talk, he showed and discussed real-time results

made by Alexander Bauer (and presented at the 9th Real Time Linux

Workshop) and his own.

In the end, this talk happened to be highly technical, but very

interesting for the one who wanted to discover how the latency tracer

could be used, and the kind of problems one can face when setting up

and using such an instrumentation tool.

Kernel size report and Bloatwatch update, Matt Mackall

Link to the video

(49 minutes, 146 megabytes).

Matt Mackall founded the Linux Tiny project in

2003, is the author of SLOB, a more space-efficient alternative

to SLAB, the kernel's memory allocator, and of other

significant improvements towards reducing the code size of the Linux

kernel. He naturally made an update of the size of the kernel, and

announced a new version of his bloat-tracking tool, Bloatwatch.

Matt Mackall founded the Linux Tiny project in

2003, is the author of SLOB, a more space-efficient alternative

to SLAB, the kernel's memory allocator, and of other

significant improvements towards reducing the code size of the Linux

kernel. He naturally made an update of the size of the kernel, and

announced a new version of his bloat-tracking tool, Bloatwatch.

To start with, Matt Mackall explained why all that attention is

paid on size. He said that it of course matters for the embedded

people, become memory and storage are expensive relative to the price

of an embedded device, and that a smaller kernel means cheaper device,

and hence more room for applications. But Matt also said that the rest

of the world now cares about code size, because even if memory and

storage are cheap, the speed ratio between CPU cache and memory

increases, which means that smaller code allows to fit more code in

cache lines, allowing performance improvements. Matt Mackall is

certainly correct with that statement, but the issue is that the code

size reduction is focused on hot paths, not on the overall code

size.

According to Mackall, the reason for the kernel grow are

many : new features, improved correcness, robustness, generality

and diagnostics. He then gave an absolutely impressive report on the

amount of changes that occured during the last year. In April 2007,

Linux 2.6.21 was the stable version, it had 21.615 files and 8.24

millions lines of code. In April 2008, time of the conference, Linux

2.6.25-rc8 was the latest available version (probably very close to

the final 2.6.25), and it has 23.811 files and 9.21 millions lines of

code. 37.033 changesets were committed to the kernel, from around

2.400 different contributors, contributing to the change of 18.165

files (almost of all files in the kernel have been touched !), to the

addition of 2.24 millions lines and the removal of 1.25 millions

lines. Matt concludes : « a lot has happened ».

He then mentionned a few notable changes in 2007, concerning the

subjects he cares : SLUB, another alternative to SLAB, is now the

default allocator, SLUB and SLOB have seen their efficiency improved,

greater attention is paid to cache footprint issues, increase usage of

automated testing, pagemap and PSS to monitor userspace (work that has

been merged in 2.6.25 and that allows to understand precisely

userspace memory consumption), and the revival of the Linux-Tiny

project, now maintained by Michael Opdenacker.

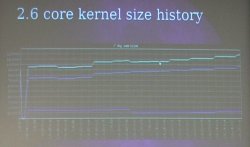

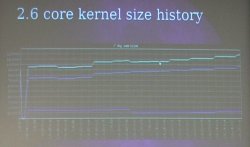

Mackall then entered the

core of the subject : kernel code size. With all the

architectures, drivers and configuration options, it's difficult to

measure the kernel code size increase (or decrease), so Matt proposed

a simple metric : measure the size of an

Mackall then entered the

core of the subject : kernel code size. With all the

architectures, drivers and configuration options, it's difficult to

measure the kernel code size increase (or decrease), so Matt proposed

a simple metric : measure the size of an allnoconfig

configuration for the x86 architecture. The

allnoconfig kernel Makefile target allows to create a

minimalistic configuration, with no network, no filesystems, no

drivers, only the core kernel features. Matt then showed a graph of

the kernel size in that configuration, from 2.6.13 (released two and

half years ago) and now. And he said, « we can see a pretty

steady and obvious increase », which we can obvisouly see on

the graph. Most of the growth is due to code increase, the data part

of the kernel hasn't increased in the last years.

The graph showed an increase of 28% on the kernel size over the

last two and half years. Over the last year, between 2.6.21 and

2.6.25-rc8, the kernel size of the same allnoconfig has

increased from 1.06 megabytes to 1.21 megabytes, a 14% increase. He

said that he made some experiments on more realistic kernel

configurations, and ignoring variations in configuration options over

the kernels, the kernel size increase was pretty much the same so he

thinks the allnoconfig metric is good enough.

He then gave some nice numbers about the size increase : it

currently increases at a rate of 400 bytes per day or 4 bytes per

change (one or two instructions). The average function size is around

140 bytes, so he concludes that we would need to take out of the

kernel three functions every day to keep the core from

growing !

To keep the kernel small, his biggest advise is to review the code

before it goes in. Insist to have new functionnalities under

configuration options, because, as he said : « I don't

need processes namespaces on my phone ». And more generally,

he said that the kernel community currently lacks code reviewers. He

proposed to continue working on inlining and code duplication

elimination : code inlining used to be popular in the kernel

community, but it is not longer useful with modern architectures. The

biggest issue is that a lot of functions are defined in header files,

and are then included in thousands of C files so that they are

instantiated in every object file. And then, Matt thinks that there is

a need to automate the size measurement to find worst offender in

existing code.. which made a perfect transition to the next topic of

his talk : Bloatwatch 2.0.

Two years ago, at the same conference, he presented Bloatwatch

1.0. The new version is rewritten from scratch, with many

improvements :

- easy to customize for your kernel configuration so that

everybody can run Bloatwatch on his specific configuration

- statistics for both built-in and modular code

- delve down into individual object files

- improved filtering of symbols

- greatly cleaned-up code

One can get Bloatwatch from its Mercurial repository,

using

hg clone http://selenic.com/repo/bloatwatch

or grab the tarball, at http://selenic.com/repo/bloatwatch/archive/tip.tar.gz.

Matt then went

one making a demo of Bloatwatch. On one hand, Bloatwatch is a set of

scripts to compile a kernel according to a configuration, and fill a

database with the results. On the other hand, it is a Web application

that allows to navigate through the results, generate nice and fancy

graphs, compare sizes between kernel versions, for the total kernel,

or for any subsystem, object file or even function.

Matt then went

one making a demo of Bloatwatch. On one hand, Bloatwatch is a set of

scripts to compile a kernel according to a configuration, and fill a

database with the results. On the other hand, it is a Web application

that allows to navigate through the results, generate nice and fancy

graphs, compare sizes between kernel versions, for the total kernel,

or for any subsystem, object file or even function.

He said that building the whole database for

allnoconfig for several years of stable kernels takes a

few hours on a normal laptop, and doing the same with

defconfig takes about a day. Which means that rebuilding

the database for a given configuration is something anyone can do

pretty easily.

In a few seconds, he demonstrated how to find the specific source

of a bloat. He pointed down the sysctl_check.code file,

that apperead during the last year, and which weights 25 kilobytes of

code. And thanks to the link to the revision control system of the

kernel, he was able to find the description of the original patches in

a few seconds, which gave an insight on the purpose of the change. In

fact, it happened that all that stuff does binary checking on

sysctl arguments, something we probably don't need on

your phone, he said. So it's probably a good candidate for a

configuration option.

Bloatwatch appears to be a great tool for measuring the kernel size

increase, and to analyze the source of that increase. Now, some effort

should probably be set up to communicate these informations to the

kernel developer community in one way or another.

Every Microamp is sacred - A dynamic voltage and current control

interface for the Linux Kernel, Liam Girdwood

Link to the video

(35 minutes, 71 megabytes) and the slides.

Liam Girdwood works for a company

called Wolfson

Microelectronics and discussed the creation of a kernel API for

voltage and current regulators controls. Before going into the kernel

framework itself, he started by providing an introduction to regulator

based systems, assuming that everyone is not necessarly familiar with

such systems, which indeed was true.

Liam Girdwood works for a company

called Wolfson

Microelectronics and discussed the creation of a kernel API for

voltage and current regulators controls. Before going into the kernel

framework itself, he started by providing an introduction to regulator

based systems, assuming that everyone is not necessarly familiar with

such systems, which indeed was true.

The power consumption in semiconductors has two components :

the static one and the dynamic one. The static one is smaller that the

dynamic one when the device is active, but is the bigger source of

power consumption when the device is inactive. The dynamic one

corresponds to the activity of the device : signals switching,

analog circuits changing state, etc. The power consumption grows

linearly with the frequency, and grows with the square of the

voltage. See this

Wikipédia page on power optimization for more informations. Liam

concluded that general introduction by saying that regulators can be

used to save both static and dynamic power.

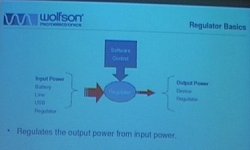

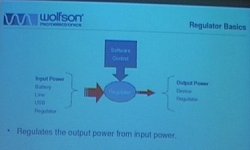

Then, he went on to

present the global picture of a regulator. It is a piece of hardware

that takes an input power (from a battery, line, USB or another

regulator), and that outputs a power (to a device or another

regulator). This piece of hardware is controlled by software, so that

we can control how the output power will be. It is possible to

instruct the regulator to generate a 1.8V output power when the input

source is 5V, or to limit the current to 20mA, for example. The whole

purpose of the regulator framework is to provide a generic software

framework for controlling this kind of devices.

Then, he went on to

present the global picture of a regulator. It is a piece of hardware

that takes an input power (from a battery, line, USB or another

regulator), and that outputs a power (to a device or another

regulator). This piece of hardware is controlled by software, so that

we can control how the output power will be. It is possible to

instruct the regulator to generate a 1.8V output power when the input

source is 5V, or to limit the current to 20mA, for example. The whole

purpose of the regulator framework is to provide a generic software

framework for controlling this kind of devices.

After that, he introduced the abstraction of power

domains. A power domain is a set of devices and regulators that

get their input power from a regulator, a switch or another power

domain, so that power domains can be chained together. Power

constraints can also be applied to power domains to protect the

hardware.

Then, in order to get into more concrete examples, he started

describing the system architecture of one of their Internet

Tablets. It has the usual components : CPU, memory, NOR flash,

audio codec, touchscreen, LCD controller, USB, Wifi and other

peripherals. Then, after showing this block diagram, he presented the

same block diagram, with all the regulators. Each device can be

controlled by one or several power regulators. The whole purpose of

the regulator framework is to control all these regulators, and so he

went on with a discussion of the framework itself.

The general goal of the regulator framework is to « provide

a standard kernel interface to control voltage and current

regulators ». It should allow systems to dynamically control

power regulator powerouput in order to save power, with the ultimate

goal of prolonging battery life, of course. The kernel framework to

control all that is divded in four interfaces :

- consumer interface for device drivers

- regulator driver interface for regulator drivers

- machine interface for board configuration

- sysfs interface for userspace

The consumers are the clients of the regulators, i.e the drivers

controlling a device that get its current from a regulator. The

consumers are constrained by the power domain in which they are :

they cannot request more that the limits that have been set for their

power domain. They defined two types of consumer : the static

ones (that just want to enable or disable the power source), and the

dynamic ones (that want to change voltage or current limit).

The consumer API is very similar to the clock API, he

said. Basically, a device driver starts accessing a regulator

using :

regulator = regulator_get(dev, "Vcc");

where dev is the device and "Vcc" a

string identifying the particular regulator we would like to

control. It returns a reference to a regulator, that should be at some

point released, using :

regulator_put(regulator);

Then, the API to enable or disable is as simple as :

int regulator_enable(regulator);

int regulator_disable(regulator);

int regulator_force_disable(regulator);

regulator_enable() will actually enable the regulator

on, and keep track of a reference count, so that the regulator will

actually be disabled only after the corresponding number of calls to

regulator_disable().

regulator_force_disable(), as its name says, allows to

disable a regulator even if the reference count is non-zero. A status

API is also available in the form of the int

regulator_is_enabled(regulator) function.

Then, the voltage API looks like :

int regulator_set_voltage(regulator, int min_uV, int max_uV);

After checking the constraints, the referenced regulator will

provide power with a voltage inside the boundaries requested by the

consumer, between min_uV (minimal voltage in micro-volts)

and max_uV. The regulator will actually choose the

minimum value that it can provide and that is in the range requested

by the consumer. The voltage actually choosen by the regulator can be

fetched using int regulator_get_voltage(regulator).

The current limit API is similar :

int regulator_set_current_limit(regulator, int min_uA, int max_uA);

int regulator_get_current_limit(regulator);

The regulators are not 100%

efficient, their efficiency vary depending on load, and they often

provide several modes to increase their efficiency. He gave the

example of a regulator with two modes : normal mode, pretty

inefficient for low current values, but that covers the full range of

current values, and an idle mode, more efficient for low current

values, for that cannot provide more current than a given limit

(smaller than the one in normal mode). So, for example, with a

consumer of 10 mA, the efficiency would be 70% in normal mode,

consuming 13 mA and 90% in idle mode, consuming 11 mA, thus saving 2

mA. So, there is an API to set the optimum mode for a given current

value :

The regulators are not 100%

efficient, their efficiency vary depending on load, and they often

provide several modes to increase their efficiency. He gave the

example of a regulator with two modes : normal mode, pretty

inefficient for low current values, but that covers the full range of

current values, and an idle mode, more efficient for low current

values, for that cannot provide more current than a given limit

(smaller than the one in normal mode). So, for example, with a

consumer of 10 mA, the efficiency would be 70% in normal mode,

consuming 13 mA and 90% in idle mode, consuming 11 mA, thus saving 2

mA. So, there is an API to set the optimum mode for a given current

value :

regulator_set_mode();

regulator_get_mode();

regulator_set_optimum_mode();

Regulators can also notify software of events, such as failure or

over temperature :

regulator_register_notifier();

regulator_unregister_notifier();

This is all the API one can use in device drivers to handle the

relation with regulators.

Then, he switched to the topic of writing a regulator driver. The

API is certainly very similar to other kernel APIs. They must first be

registered to the framework before consumers can use them :

struct regulator_dev *regulator_register(struct regulator_desc *desc,

void *data);

void regulator_unregister(struct regulator_dev *rdev);

The events can propagated to consumers, thanks to the notifier call

chain mechanism. Every consumer that registered a callback using

regulator_register_notifier() will be notified if the

following function is called by a regulator driver :

int regulator_notifier_call_chain(struct regulator_dev *rdev, unsigned

long event, void *data);

The regulator_desc structure must give a few

information about the regulator (name, type, IRQ, etc.), but most

importantly, must contain a pointer to a regulator_ops

structure. It is pretty much a 1:1 mapping of the consumer

interface :

struct regulator_ops {

/* get/set regulator voltage */

int (*set_voltage)(struct regulator_cdev *, int uV);

int (*get_voltage)(struct regulator_cdev *);

/* get/set regulator current */

int (*set_current)(struct regulator_cdev *, int uA);

int (*get_current)(struct regulator_cdev *);

/* enable/disable regulator */

int (*enable)(struct regulator_cdev *);

int (*disable)(struct regulator_cdev *);

int (*is_enabled)(struct regulator_cdev *);

/* get/set regulator operating mode (defined in regulator.h) */

int (*set_mode)(struct regulator_cdev *, unsigned int mode);

unsigned int (*get_mode)(struct regulator_cdev *);

/* get most efficient regulator operating mode for load */

unsigned int (*get_optimum_mode)(struct regulator_cdev *, int input_uV,

int output_uV, int load_uA);

};

After this short description of the regulator driver interface, he

described the machine driver interface. It is basically used to glue the

regulator drivers with their consumers for a specific machine

configuration. It describes the power domains : « regulator

1 supplies consumers x, y and z », power domain suppliers :

« regulator 1 is supplied by default (Line/Battery/USB) » or

« regulator 1 is supplied by regulator 2 » and power domain

constraints : « regulator 1 output must be between 1.6V and

1.8V ».

To give a concrete example, he said lets take a NAND flash whose

power is supplied by the LDO1 regulator. To attach the regulator to

the "Vcc" supply pin of the NAND, we use the followind call :

regulator_set_device_supply("LDO1", dev, "Vcc");

It will associate the regulator named LDO1 (as given

in the regulator_desc structure) to the Vcc

input of a given device. Then that device driver is able to use the

regulator_get() to get a reference to its regulator and

then control it.

Then, the machine driver can specify constraints on power domains,

using the regulation_constraints that can be associated

to a given regulator using

regulator_set_platform_constraints().

Finally, the machine driver is also responsible for mapping

regulators to regulators, when one regulator are supplied by other

regulators. It is done using the regulator_set_supply()

function, which takes the name of two regulators as arguments, the

supplier regulator, and the consumer regulator. Of course, it is up to

the machine specific code to glue up everything properly.

Then, he described the sysfs interface, which exports

regulator and consumer information to userspace. It is currently

read-only, and Liam doesn't seem at the moment a good reason to switch

it to read-write. One can access information such as voltage, current

limit, state, operating mode and constraints, which could be used to

provide more power usage information to PowerTOP, for example.

After this API description, he gave some real world

examples. First, cpufreq, which allows to scale CPU frequency

to meet processing demands. He says that voltage can also be scaled

with frequency : increased with frequency to increase performance

and stability or decreased with frequency to save power. And that can

be done with the regulator_set_voltage() API. In

cpuidle, you can imagine changing the operating mode of the

regulator that supplies current to the CPU in order to switch a more

efficient mode.

He then gave the example of LCD backlights, which usually consume a

lot of power. When it's possible to reduce brightness, then power

reduction is only possible, and that can be achieved using the

regulator_set_current_limit() API, particularly for

backlights using white LEDs, in which brightness can be changed by

changing the current.

In the audio world as well, improvements can be made. Audio

hardware consumes analog power even when there is no audio

activity : power can be saved by switching off the regulators

supplying the audio hardware. We might also think of switching off the

components that are not used, and he gave the example of the FM-turner

when you're listening to MP3's or the speaker amplifier that can be

turned off when headphones are used. And mentionned the relevant

API : regulator_enable() and

regulator_disable(). Same goes for NAND and NOR flashes

that consume more power during I/O than when they are idle, so it is

possible to switch the operating mode of the regulators to take

advantage of more efficient mode for low current values. He pointed

out the fact that flashes have power consumption information in their

datasheets, and that they could be used in the flash driver to

properly call regulator_set_optimum_mode() to set the

best possible mode for the current power consumption.

The status of this work is that the code is working on several

machines. It supports several hardware : Freescale MC13783,

Wolfson WM8350 and WM8400. They are working with the -mm kernel by

providing patches to Andrew Morton, and they already posted the code on the

Linux Kernel Mailing List. They also have a webpage for

their project, and the code is available in a git

repository.

Using Real-Time Linux, Klaas van Gend

Link to the video

(53 minutes, 263 megabytes) and the slides.

This talk of Klaas van Gend, Senior Solutions Architect at

Montavista Europe, was subtitled Common pitfalls, tips and

tricks. His talk is a presentation of the real-time version of the

Linux kernel, clarifications about various misconceptions on

real-time, and advises.

He started by

presenting both faces of Klaas : Klass-the-Geek, who started

programming at 13, first encountered Linux in 1993 and is a software

engineer since 1998, and Klaas-the-Sales-Guy, who joined Montavista as

FAE in 2004 and is in charge of the UK, Benelux and Israel

territory.

He started by

presenting both faces of Klaas : Klass-the-Geek, who started

programming at 13, first encountered Linux in 1993 and is a software

engineer since 1998, and Klaas-the-Sales-Guy, who joined Montavista as

FAE in 2004 and is in charge of the UK, Benelux and Israel

territory.

Originally, Linux is designed to be fair, like the other

Unixes : the CPU has to be shared properly between all processes,

with a fair scheduling. However, in the case of real-time systems, you

don't usually care about fairness. So a lot has to be done to get

real-time capabilities to the Linux kernel, and that work is

happening, and has been happening for a long time in the

-rt version of the Linux kernel, maintained as a separate

patch. His slide also mentionned some progress made on the mainline

kernel : originally, only userspace code was preemptible, then

Robert Love added preemption to the kernel, and Ingo Molnar added

voluntary preemption. The O(1) scheduler, which allows to decide which

task should be run next in a constant time, was also mentionned.

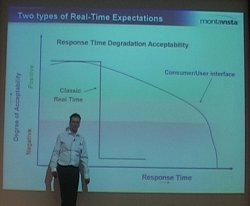

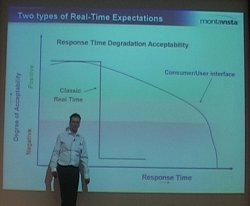

He then went on

with a definition of real-time : « Ok, we have a deadline

and if we don't make the answer within the deadline... Sorry we don't

care anymore ». As an example, he said : « if the

airbag doesn't blow in time or is only half-way blown, too bad :

you're dead ». In contrast, he said, if after a mouse click the

system only reacts after half a second, that's annoying, but it

works. And his words were strengthen with a nice slide showing that

the degree of acceptability of the response time only slowly decreases

for consumer/user interface, but flaws down completely for a classic

real time system.

He then went on

with a definition of real-time : « Ok, we have a deadline

and if we don't make the answer within the deadline... Sorry we don't

care anymore ». As an example, he said : « if the

airbag doesn't blow in time or is only half-way blown, too bad :

you're dead ». In contrast, he said, if after a mouse click the

system only reacts after half a second, that's annoying, but it

works. And his words were strengthen with a nice slide showing that

the degree of acceptability of the response time only slowly decreases

for consumer/user interface, but flaws down completely for a classic

real time system.

Main assumption is Real Time Linux : the higest priority task

should go first, « always », he said. Which means that

everything should be pre-emptable and that nothing should keep higher

priority things from executing. He said that lots of things had to be

changed in the kernel to get this assumption, and one of the first

thing was spinlock.

The original Linux UP spinlock basically disables interrupts :

nothing else can interrupt during the critical section, which is not

real-time-friendly at all. And the original SMP spinlock basically

busy wait for another CPU to release the lock, which is not necessarly

performance-friendly. In order to go to real-time, something had to be

done with spinlocks : introduce sleeping spinlocks, so

that instead of busy-waiting, threads waiting for the lock would go to

sleep, and no interrupt would be disabled. Spinlocks are turned into

mutexes.

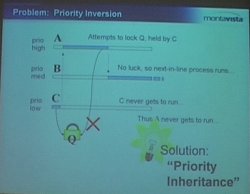

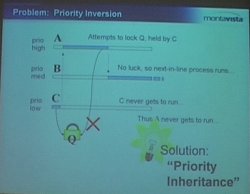

Another

problem is the priority inversion problem, a fairly classical problem

in synchronization and scheduling litterature, which can lead to the

situation where an high priority process cannot run because it is

blocked by a low priority process. We have three processes : A, B

and C. A has the highest priority, B a medium priority and C a low

priority. C holds a lock Q. After some time, task A needs that lock Q,

but it is still held by C, so A cannot run. And because B is runnable

and its priority is higher than the priority of C, then B will run,

and run, and run, and the lock will never be released, or only when B

is done executing its code. The solution to this problem is known as

priority inheritance. In our case, the priority

inheritance mechanism would increase the priority of C to the

priority of A when A needs the lock held by C, so that C can run

instead of B, release the lock, and allow A to get it. Work on

priority inheritance has been done inside the

Another

problem is the priority inversion problem, a fairly classical problem

in synchronization and scheduling litterature, which can lead to the

situation where an high priority process cannot run because it is

blocked by a low priority process. We have three processes : A, B

and C. A has the highest priority, B a medium priority and C a low

priority. C holds a lock Q. After some time, task A needs that lock Q,

but it is still held by C, so A cannot run. And because B is runnable

and its priority is higher than the priority of C, then B will run,

and run, and run, and the lock will never be released, or only when B

is done executing its code. The solution to this problem is known as

priority inheritance. In our case, the priority

inheritance mechanism would increase the priority of C to the

priority of A when A needs the lock held by C, so that C can run

instead of B, release the lock, and allow A to get it. Work on

priority inheritance has been done inside the linux-rt

tree, but has finally been merged

into mainline in 2.6.18.

The next problem discussed by Klaas come from the named

semaphores mechanism. These are semaphores that appear on the

filesystem, so that they can be used by several non-related processes

(processes with no parent-child relationship or living in the same

address space). The problem with named semaphores is that when a

process holding the semaphore dies, the semaphore is not automatically

released and any other process trying to get the semaphore will be

stuck... until a system reboot. The solution to that is called

robust mutexes, which allow to automatically release mutexes

when a process dies. It has been merged in 2.6.17, and covered by Linux Weekly News.

Then, Klaas quickly covered the topic of priority

queues. Traditionnaly, the Linux kernel handled mutex queues in a

FIFO-order: the first waiting process gets the mutex when it is

released by another process. However, on real-time system, you want

the mutex to be assigned to the highest priority waiting process. This

is not fair for the other processes, but as explained by the speaker

at the beginning of his talk, real-time and fairness are not

necessarly compatible. The solution to this problem is called

priority queues : processes are ordered by priority in

waiting lists. This is implemented by the rtmutex code in

the Linux kernel (see kernel/rtmutex.c),

which is used by the Futex facility available in userspace (see

futex(7) for more details), and used by the glibc

to implement mutexes. The rtmutex relies on the

plist library in the kernel (see lib/plist.c).

Klaas van Gend then discussed the issues of the standard IRQ

handling mechanism in Linux. In the regular kernel, IRQ and tasklets

are handled in priority over any task in the system, even the

highest-priority ones. This means that the execution of an high

priority task can be delayed for an unbounded time because of any IRQ

coming from the hardware, even interrupts we don't care about. The

solution to this problem, only available in the linux-rt

tree as of today, is called threaded interrupts. The idea is to

move the interrupt handlers to threads, so that they become entities

known by the scheduler. Once known by the schedulers, these entities

can be scheduled (i.e delayed) and we can assign priority to them. To

illustrate the need for such a feature, Klaas gave the example of a

customer who builds a big printer. On this printer, the high-priority

task is to push informations to the engine, otherwise the user will

get white bands on the paper. And this process should not be disturbed

by any other process, such as getting new printing jobs. He wanted to

highlight the fact that threaded interrupts are actually in use

and are useful.

Klaas then concluded : « essentially, those are the

basic mechanisms in use to make Linux realtime. Does it help ? Yes it

does. ». And he switched to the Results section of his

presentation. He started with measurements of the interrupt

latency, and compared the results of different preemption modes

(none, desktop and RT) on an IXP425 platform using a 2.6.18

kernel. With preempt none, the minimum latency is 4 microseconds,

average is 6 and maximum is 9797 microseconds. With preempt desktop,

the minimum latency is 5, average is 10 and maximum is 2679. With

preempt RT, the minimum is 6, the average 7 and the maximum 349

microseconds. With an higher-end processor (FreeScale 8349 mITX), the

results are better: maximum latency of 3968 microseconds with preempt

none, 1604 with preempt desktop and 53 microseconds with preempt

RT. And he said that with an Intel Core 2 Duo, they managed to lower

the maximum latency to 30 microseconds. For more results, he suggested

requesting the Real Time whitepaper from Montavista.

After this short

result section, the speaker switched to the final part of his talk,

entitled Common mistakes and myths. The first myth is that

people are confusing fast and determinism. He cited

quotes such as « I need real time because my system needs to

be fast » or « I want to have the best performance

Linux can do ». But he said «NO !», real time does not mean

highest throughput, it means more predictable. He even said that

efficiency and responsiveness are inversely related. For example, the

real-time preemption code adds some overhead (spinlocks are replaced

by mutuxes but mutexes are much more heavy-weight than spinlocks,

priority inheritance increases task switching and worst case execution

time, etc.). He cited benchmarks that measured a decrease of 20% in

the network through of a -RT kernel when compared to a regular

kernel.

After this short

result section, the speaker switched to the final part of his talk,

entitled Common mistakes and myths. The first myth is that

people are confusing fast and determinism. He cited

quotes such as « I need real time because my system needs to

be fast » or « I want to have the best performance

Linux can do ». But he said «NO !», real time does not mean

highest throughput, it means more predictable. He even said that

efficiency and responsiveness are inversely related. For example, the

real-time preemption code adds some overhead (spinlocks are replaced

by mutuxes but mutexes are much more heavy-weight than spinlocks,

priority inheritance increases task switching and worst case execution

time, etc.). He cited benchmarks that measured a decrease of 20% in

the network through of a -RT kernel when compared to a regular

kernel.

He then went one with a list of mistakes :

- Forgetting to recompile. When switching to

-rt, all

kernel files need to be recompiled because of the complex internal

changes that are involved by the switch to

-rt. However, the userspace ABI doesn't change, so you

don't have to recompile the glibc or the userspace applications. But

if you use third-party modules, you'll have to recompile

them. Another drawback of third-party binary kernel

modules !

- Forgetting to enable robustness and priority-inheritance in

userspace. Userspace mutexes do not automatically have the

robustness and priority-inheritance properties. They must be enabled

by doing

pthread_mutex_t mutex;

pthread_mutexattr_t mutex_attr;

pthread_mutex_attr_init(&mutex_attr);

pthread_mutexattr_setprotocol(&mutex_attr, PTHREAD_PRIO_INHERIT);

pthread_mutexattr_setrobust_np(&mutex_attr, PTHREAD_MUTEX_ROBUST_NP);

pthread_mutex_init(&mutex, &mutex_attr);

- « Running at prio 99 froze my system ». If a

process running a top priority runs forever, then the system will be

freezed. So an infinite-loop process with lock your system, even if

you call

sched_yield(). sched_yield() will

simply yield the CPU to the highest-priority runnable process :

you !.

He then gave some advises on how to design the system. One should

not set the highest priority or even realtime priority to all the

processes in the system, otherwise you are no longer real-time. And

the realtime tasks should be carefully designed to run in a fairly

limited time, so that the rest of the system can still execute. If you

have a collection of realtime processes, their execution time must of

course match with the timing requirements that you have. He suggested

to have only one or two high priority tasks in the system, otherwise

things start to be very complicated to design.

One myth he wanted to fight first is the myth that real time is

hard. He said that it is not as hard as many tend to say and to think

it is. The second myth he wanted to fight is the rumor that real-time

is only pushed by the embedded community. It is also strongly pushed

by the audio community, and can be useful for games as well.

He went back to a

mistake made by a customer. Even after switching to a real-time

enabled 2.6 kernel, that customer still missed some bytes upon

reception on serial ports on his Geode x86-like board. It turned out

that it was caused by calls to the BIOS used for VGA buffer scrolling

and VGA resolution switching. These calls can disable interrupts for

an unbounded amount of time, not controlled by the Linux kernel. He

also mentionned the problem of

He went back to a

mistake made by a customer. Even after switching to a real-time

enabled 2.6 kernel, that customer still missed some bytes upon

reception on serial ports on his Geode x86-like board. It turned out

that it was caused by calls to the BIOS used for VGA buffer scrolling

and VGA resolution switching. These calls can disable interrupts for

an unbounded amount of time, not controlled by the Linux kernel. He

also mentionned the problem of printk() on serial

port. printk() on a serial line can block waiting for the

transmission buffer of the UART to be empty after transmitting the

bytes to the other end. And this can take an unbounded amount of

time. So he suggested disabling printk() completely when

one has real-time issues.

After this suggestion, he switched to another topic : the

relation between RT and SMP concerns when doing driver development. He

said that both RT and SMP have similar requirements : in RT any

process can be preempted at any time, which is very similar to

multi-processor issues, where the same code can run simultaneously on

different cores. All requirements for SMP-safeness also apply to RT,

and RT and SMP share the same advanced locking, he said. He also

mentionned that the deadlock detection code introduced by the

-rt people already led to the fix of many SMP bugs in

the kernel.

Then he discussed the problem of swapping in the context of a real

time system. What happens if your real time task code or data gets

swapped to disk because of memory pressure in your system ? The

latencies would be horrible. The solution he mentionned to this

problem is the usage of the mlockall() system

call :

mlockall(MCL_CURRENT | MCL_FUTURE);

But it warned that this should already be done on small process,

because all memory pages of the process will be locked into

memory : code, data and libraries.

And to complete his talk he highlighted the fact that the Linux

Real Time kernel comes with no warranty. Even though is has been

thorougly tested over the years by the kernel community and companies

such as Montavista, the Linux kernel has several millions of lines of

code, and nobody can prove that it will work correctly in all

situations. One has to verify that it works well for his particular

use cases.

To conclude, he said that Linux used to be fair, which is not good

for real-time. Montavista has worked on RT behaviour since 1999, but

true real time only appeared in Linux in 2004, with interrupt

latencies below 50 microseconds on certain platforms. However, the

real-time patch is still being merged into mainline kernel, and real

time system design has its challenges... just like programming in

COBOL, he said. He ended with a famous quote of Linus

Torvalds « Controlling a laser with Linux is crazy, but

everyone in this room is crazy in his own way. So if you want Linux to

control an industrial welding laserr, I have no problem with your

using PREEMPT_RT ». And Klaas made the transition to the

questions session with a funny Windows Blue Screen of Death.

During the question session, there have been questions about the

interaction between memory allocation and real time, questions about

predictions on the merge of the remaining -rt features to

the mainline kernel (with some insights by Matt Mackall on that

topic), a question about the interaction between real-time and the I/O

scheduling, another topic on which Matt Mackall gave some interesting

insights.

In the end, that presentation wasn't about anything really new, but

gave a well-presented overview of the features needed in the Linux

kernel to answer the needs of real-time users, and a good summary of

the first pitfalls one could fall in while doing real time

programming.

Power management quality of service and how you could use it in

your embedded application, Mark Gross

Link to the video

(57 minutes, 401 megabytes) and the slides.

Mark Gross, who works at the Open Source Technology Center of

Intel, gave a talk about power management quality of service

(PM_QOS), a new kernel infrastructure that has been

merged in 2.6.25 (see the commit

and the interface

documentation).

The

starting problem for Mark Gross work in the current architecture of

power management, where the power mangament policy implementation is

extracted away for the drivers (who know the hardware the best) to a

centralized policy manager, creating a dual point of maintenance of

device power/performance knowledge : some in the driver, some in

the policy manager. In his opinion, it « removes all hope of

good abstractions or stable and useful PM API's ».

The

starting problem for Mark Gross work in the current architecture of

power management, where the power mangament policy implementation is

extracted away for the drivers (who know the hardware the best) to a

centralized policy manager, creating a dual point of maintenance of

device power/performance knowledge : some in the driver, some in

the policy manager. In his opinion, it « removes all hope of

good abstractions or stable and useful PM API's ».

That's the reason for which PM QoS was created. The goal is

to provide a coordination mechanism between the hardware providing a

power managed resource and users with performance needs. It's

implemented as a new kernel infrastructure to facilitate the

communication of latency and throughput needs among devices, system

and users. Automatic power management is then then enabled at the

driver with coordinated device throtling given the QoS expectations on

that device.

He then presented areas where PM QoS would be useful in the

kernel. First in the cpu-idle infrastructure, to take

DMA latency requirements into account when switching to deeper

C-states. He also cited issues with the ipw2100 driver or sound

drivers when C-state latencies are large.

PM QoS first implements in pm_qos_params.c a

list of parameters, which are currently just :

cpu_dma_latency, network latency and network

throughput. These are exported both to the kernel and to

userspace. PM QoS maintains a list of pm_qos requests

for each parameter, along with an aggregated performance requirement

and maintains a notification tree, for each parameter. Inside the

kernel, it provides an API to register to notifications of performance

requests and target changes. To userspace, it provides an interface

for requesting QoS.

When an element is added or changed inside the list of

pm_qos of a given parameter, the corresponding aggregate value

is recomputed. If it changed, then all drivers registered for

notification on that parameter are notified.

From the userspace point of view, PM QoS appears as a set of

character device files, one for each PM QoS parameter. When an

application opens one of these files, then a PM QoS request

with a default value is registered. The application can later change

the value by writing to the device file. Closing the device file will

remove the request in the kernel, so that if the application crashes,

the cleanup is done automatically by the kernel. Mark then showed a

simple Python program to use that user interface :

#!/usr/bin/python

import struct, time

DEV_NODE = "/dev/network_latency"

pmqos_dev = open(DEV_NODE, 'w')

latency = 2000

data = struct.pack('=i', latency)

pmqos_dev.write(data)

pmqos_dev.flush()

while(1):

time.sleep(1.0)

Mark Gross then described the in-kernel API. A driver can poll the

current value for a parameter using :

int pm_qos_requirement(int qos);

but of course, most drivers will probably be more interested in the

parameter notification mechanism. They can subscribe (and unsubscribe)

to a notification chain using :

int pm_qos_add_notifier(int qos, struct notifier_block *notifier);

int pm_qos_remove_notifier(...);

To create new PM QoS parameters, one will have to modify the

pm_qos_init() code in

kernel/pm_qos_params.c.

After describing the

consumer side of the API, he described the producer

side of the API, that allows to instruct other device drivers to

respect certain latency or throughput requirements (just like the

userspace API presented previouslsy). This API is a set of three

functions :

After describing the

consumer side of the API, he described the producer

side of the API, that allows to instruct other device drivers to

respect certain latency or throughput requirements (just like the

userspace API presented previouslsy). This API is a set of three

functions : pm_qos_add_requirement(int qos, char *name, s32

value) to add a requirement to a parameter list,

pm_qos_update_requirement(int qos, char *name, s32 value)

to update it, and pm_qos_remove_requirement(int qos, char

*name) to remove it.

At the end of the presentation, he gave the example of using PM

QoS within the iwl4965 wireless adapter driver. This is a

work in progress that he is working on with one of the iwl4965

developers. The chipset has six high level power configurations

affecting the powering of the antenna, how quickly it sleeps the radio

and for how long between AP-beacons, so it looks like a good

application of PM QoS network latency parameter, he said.

Currently, the power management of this device is device-specific,

through sysfs. Thanks to PM QoS, the driver could simply

register itself for pm_qos notifications of changes to

network latencies requirements, and switch to the corresponding power

management levels when needed. All other network device drivers could

do the same, so that sane user mode policy managers could be written

without knowing the exact power management details of each and every

network adapter. Mark Gross then described some details of the

implementation of PM QoS inside the iwl4965 driver.

Mark sees a lot of possibilities with such a coherent userspace

interface. Network shooter games could set network latency to zero to

disable power management. A Web browser could set it to two seconds, a

instant-messaging client to 0.5 seconds, an user mode policy manager

could adjust it when the laptop goes to battery power or switches back

to AC power, etc.

In the end, the talk was fairly short, but very interesting and

completely in-topic. Some developer invents a new API to solve a

problem, and tries to make it known, to allow other developers to use

this API in their drivers or applications, and to get feedback from

the community. Something that just happened during the long questions

and answers session that followed the talk (discussion on the current

API, its usage, etc.)

Leveraging Free and Open Source Software in a product development

environment, Matt Porter

Link to the

(45 minutes, 220 megabytes) and the slides.

In this talk, Matt Porter, who

works for Embedded Alley, wanted to explain how one can leverage Free

and Open Source Software in the development of a new product. Everyone

knows that GNU toolchains exist, that we have the Linux kernel and

standard basic root filesystems. But then, what else is there,

wondered Matt Porter ?

In this talk, Matt Porter, who

works for Embedded Alley, wanted to explain how one can leverage Free

and Open Source Software in the development of a new product. Everyone

knows that GNU toolchains exist, that we have the Linux kernel and

standard basic root filesystems. But then, what else is there,

wondered Matt Porter ?

In order to make his talk more concrete, he proposed to discuss a

case study, and follow the following steps : define application

requirements, break down requirements by software components, identify

software components fully or partially available as FOSS and finally

integrate and extend the FOSS components with value-added software to

meet application requirements.

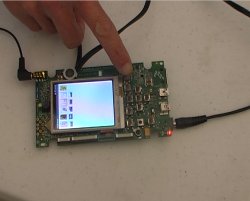

His case study was the development of a Digial Photo Frame

(DPF), on of these small devices that allows to display pictures,

play music, are wireless connected and look nice and shiny on the

dinning room table. The requirements for such a device are clear and

concise, he said, making it a good example for his presentation.

His hardware platform is a ARM SoC (with DSP, PCM audio playback,

LCD controller, MMC/SD controller, NAND controller), a 800x600 LCD

screen, a couple of nagivation buttons, MMC/SD slot, NAND flash and

speakers. The user requirements for the DPF device were

- Display to the LCD

- Detect SD card insertion, notify application of SD card

presence, and have the application catalog the photo files present

of the card

- Provide a modern 3D GUI and transitions, navigation via buttons,

configuration for slideshows, transition types, etc.

- Audio playback of MP3, playlist handling, ID3 tag display

- Support JPEG resize and rotation to support arbitrary-sized JPEG

files, dithering support for 16 bits display

Based on these requirements, he established a list of software

components that are needed

- Firmware

- OS Kernel

- I/O drivers

- Base userspace framework/applications

- Media event handler

- Jpeg library (run on ARM or DSP)

- MP3 and supporting audio libraries

- OpenGL ES library for 3D interface

- Main application

He quickly covered the obvious components : U-Boot for the firmware, Linux as the kernel, leveraging the

SD/MMC, framebuffer, input and ALSA subsystems of the kernel as I/O

drivers, use Busybox as the base

userspace framework and use OpenEmbedded as the build

system.

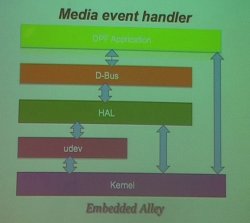

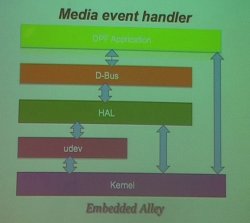

For the media

event handling, he used udev,

which receives events from the kernel when the SD card is inserted or

removed, creates device nodes according to a set of rules, and then

sends the event to the HAL

daemon. HAL, which stands for Hardware Abstraction Layer, is a

daemon to handle hardware interaction : it knows how to handle

the hardware, and can send events over >D-Bus to

notify other applications, such as the main DPF

application. D-Bus was used in their product, it is an IPC

framework used to implement a system-wide bus on which applications

can communicate with each other. In their case, the communication

between HAL and their application takes place over D-Bus : the

application subscribes to HAL events for the SD card and is notified

when something happens.

For the media

event handling, he used udev,

which receives events from the kernel when the SD card is inserted or

removed, creates device nodes according to a set of rules, and then

sends the event to the HAL

daemon. HAL, which stands for Hardware Abstraction Layer, is a

daemon to handle hardware interaction : it knows how to handle

the hardware, and can send events over >D-Bus to

notify other applications, such as the main DPF

application. D-Bus was used in their product, it is an IPC

framework used to implement a system-wide bus on which applications

can communicate with each other. In their case, the communication

between HAL and their application takes place over D-Bus : the

application subscribes to HAL events for the SD card and is notified

when something happens.

The next subject was JPEG picture handling. For JPEG decoding, they

used the libjpeg library, and for

resize and rotation, they used jpegtran. Dithering

was not supported in libjpeg or jpegtran, and instead of writing their

own code, they borrowed some code from the FIM image viewer (FIM

stands for Fbi IMproved, which is a framebuffer based image

viewer).

To support MP3 playing, they used libmad, which runs on

ARM and supports MP3 audio decoding for playback. They also used libid3 to handle the ID3

tags and be able to display them on the screen, and libm3u to handle

media playlists.

Then, he covered a more specific and technical subject : using

DSP acceleration. Using the DSP available in hardware to accelerate

JPEG and MP3 processing looks like an interesting option. First, one

needs a DSP bridge, and he mentionned

openomap.org as a good starting point

for that topic. He also mentionned using libelf to process

ELF DSP binaries, which allows for pre-runtime patching of symbols and

cross calls from DSP to ARM. He said that the general purpose

libraries such as libjpeg, jpegtran, FIM and libmad can be ported to

run portions of their code on a DSP.

For the 3D graphic

interface, they decided to use Vincent, an OpenGL ES 1.1

compliant implementation. Nokia ported the code to Linux/X11, and it

has been easily modified to run on top of the Linux framebuffer. It

can also be extended in various ways to support hardware accelerated

cursor, floating/fixed point conversions, use GPU acceleration,

etc.

For the 3D graphic

interface, they decided to use Vincent, an OpenGL ES 1.1

compliant implementation. Nokia ported the code to Linux/X11, and it

has been easily modified to run on top of the Linux framebuffer. It

can also be extended in various ways to support hardware accelerated

cursor, floating/fixed point conversions, use GPU acceleration,

etc.

He said that a complete GUI can be implemented in low-level OpenGL

ES. Font rendering can be done using the freetype library, and it

enables 3D desktop look for the interface. It also makes 3D photo

transitions possible : photos are loaded as textures, and

transitions are then managed as polygon animation and camera view

management. He also mentionned the fact that higher-level libraries

such as Clutter can be used

on top of OpenGL ES to provide higher-level interface building

tools.

Finally, he described the main DPF application, which integrates

all the FOSS components : manages media events, uses the JPEG

library to decode and render photos, handles Linux input events and

drivers OpenGL ES based GUI, manages user-selected configuration,

displays photo slideshow using selected transitions.

To conclude, he said that « good research is the key to

maximizing FOSS use ». He however warned that many components

will require extensions and/or optimization, but that smart use of

FOSS where possible will save time, money and speed product to market.

Demonstrations

At the end of the first day, some companies and projects have been

invited to demonstrate some of their work in the hall next to the main

conference room. Your editor found some of these demonstrations

particularly interesting.

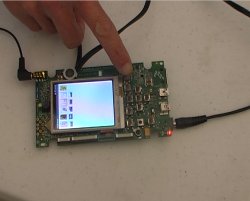

One person from Futjitsu was demonstrating Google Android on real

hardware. They ported Android from the QEMU environment provided in

Google's SDK to real environments : Freescale LMX31 PDF, a

development board, and Sophia Systems Sandgate3-P, a device which

looks like a mix of a phone and a remote controller.

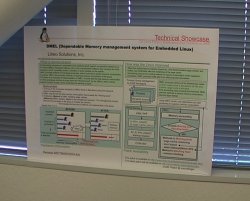

Engineers from Lineo Solutions were demonstrating their work around

memory management, and the management of out-of-memory

situations. They explored in-kernel memory mechanisms and userspace

notifications mechanisms through a signal. The latter sounded

particularly interesting, as it allows to notify applications of

memory pressure inside the kernel. The application could then free

some memory used for temporary caches for example, in order to help

the system to recover for the bad situation.

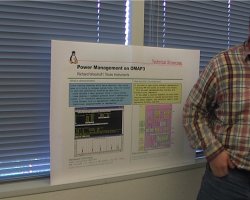

Richard Woodruff, from Texas Instrument, was demonstrating the

power management improvements they made to the Linux kernel in order

to decrease the power consumption of their OMAP3 platform. They have

been able to get very impressive results.

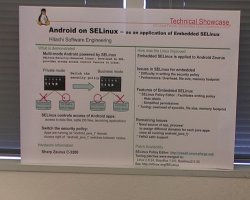

One Hitachi engineer was demonstrating the use of SELinux in

Android. SELinux was used to create to operating modes in

Android : the private mode and the business mode. In private

mode, only personal applications and data are available. In business

mode, only business applications and data are available. And the

isolation between these two worlds is enforced by SELinux.

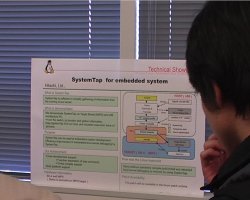

Another Hitachi engineer was demonstrating the use of SystemTap in

an embedded system. SystemTap was not designed with the

cross-compilation and host/target separation problems in mind. So they

improved SystemTap to make it more easily usable in embedded

situations : the kernel module generate by SystemTap can be

cross-compiled, then loaded to a remote target, and the results can be

gathered on the host. These improvements will soon be published.

York Sun, from Freescale Semiconductor was demonstrating a new CPU,

with interesting framebuffer capabilities. The framebuffer controller

is able to overlay in hardware several layers, which is very useful in

things such as navigation systems. York Sun gave more details about

Linux support of such a framebuffer controller in the talk entitled

Adding framebuffer support for Freescale SoCs.

Day 2

Keynote: The relationship between kernel.org development and the

use of Linux for embedded applications, Andrew Morton

Link to the video

(55 minutes, 240 megabytes) and the slides.

The second day started by a conference given by a famous special

guest : Andrew Morton. After an introduction by conference

organizer Tim Bird, Andrew started his talk entitled The relation

ship between kernel.org development and the use of Linux for embedded

applications.

His talk was already the subject of several reports,

at least one on LWN,

by Jake Edge.

Andrew Morton's talk was not technical at all, it rather discussed

how embedded companies could participate more in mainline kernel

development, what are their interests to do so, and how this can be

mutually beneficial to both the companies and the kernel

community.

Linux Tiny, Thomas Petazzoni

Link to the video

(32 minutes, 140 megabytes). Thanks to Jean Pihet, Montavista for

recording the talk.

Making a full and complete report of your editor's talk wouldn't be

very interesting, so let's let other persons do that. Just to sum up,

the talk discussed the following topics :

- Why is the kernel size important ?

- Demonstration of the fact that the kernel size is growing, in a

significant way over the years

- History, goal and current status of the Linux Tiny project

- Future work on this project

UME, Ubuntu Mobile and Embedded, David Mandala

Link to the video

(30 minutes, 145 megabytes) and the slides.

David Mandala gave a not very

technical talk about UME, Ubuntu Mobile and Embedded. He first

described the type of devices targetted by UME : the devices are

called MID, for Mobile Internet Devices. He described them as

« consumer centric devices », « task oriented

devices », offering a simple and rich experience with an

intuitive UI and an "invisible" Linux OS.

David Mandala gave a not very

technical talk about UME, Ubuntu Mobile and Embedded. He first

described the type of devices targetted by UME : the devices are

called MID, for Mobile Internet Devices. He described them as

« consumer centric devices », « task oriented

devices », offering a simple and rich experience with an

intuitive UI and an "invisible" Linux OS.

He then described Ubuntu Mobile & Embedded as a completely new

product based on Ubuntu core technology. It incorporates open source

components from maemo.org, adds new

mobile applications developed by Intel and adapts existing open source

applications for mobile devices. The challenges for UME are mainly

that applications can't fit on small screens and that applications are

designed for keyboard and mouse, not fingers and touch screen. The big

focus of UME is on these two problems, not on other embedded related

issues such as system size, boot time, memory consumption, port to

other architectures, etc. This is a point that has been raised by the

Rob Landley at the end of the talk, and it seems that at the moment,

these topics are not in the radar of the UME project.

David Mandala listed the differences between UME and the standard

Ubuntu desktop : GNOME Mobile (Hildon) is used instead of the

standard GNOME desktop, applications are optimized to fit in 4.5" to

7" touch LCD, optimizations for power consumption (with a reference to

the LPIA

acronym, which seems to stand for Low Power on Intel Architecture),

built-in drivers for WiFi, WiMax, 3G and Bluetooth. The size of the

system will be around 500 megabytes, it targets devices with more than

2 gigabytes of Flash. Not something we can call

resource-constrained.

The global architecture of Ubuntu Mobile is similar to a normal

Linux desktop : the kernel with its drivers, X11 with Cairo,

Pango, OpenGL, a networking layer, basic frameworks like Gtk, HAL,

D-Bus, Gstreamer, and then application for PIM, e-mail, web browsing,

instant messaging, etc. David Mandala also mentionned the problem of

proprietary applications with redistribution restrictions, such as

a Flash player and video codecs.